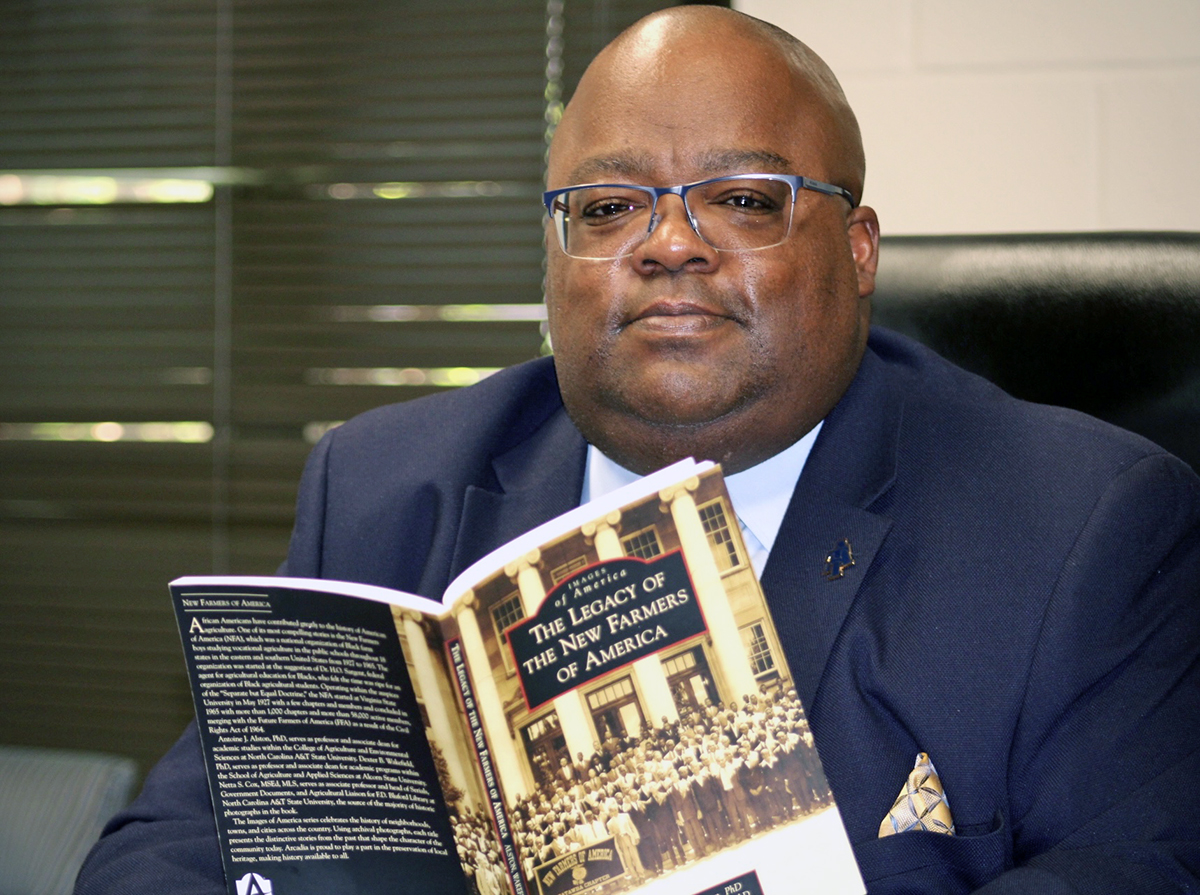

Alumnus pens book about history of New Farmers of America

Many have heard about Future Farmers of America, but few may know about New Farmers of America. Antoine Alston is out to change that.

Alston (’00 PhD agricultural education and studies), professor and associate dean within the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at North Carolina A&T State University, is anxiously awaiting May 2. That is the release date of “The Legacy of the New Farmers of America,” a historical narrative about a national organization meant for Black farm boys studying vocational agriculture in high school. Similar in structure to the Future Farmers of America, the NFA was formed in 1927 and existed until 1965, when it merged with FFA following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Through photos and narratives, the 127-page book looks at the structure and leadership of the NFA, as well as the impacts it had on the community.

Alston co-wrote the book with Dexter B. Wakefield, professor and associate dean for academic programs within the School of Agriculture and Applied Sciences at Alcorn State University, and Netta S. Cox, associate professor and head of Serials, Government Documents, and Agricultural Liaison for F.D. Bluford Library at North Carolina A&T State University.

“This book is unique and long-needed,” Alston says. “African American history has not always been told, and people need to understand how our country has evolved.”

The NFA has a special place in Alston’s heart. Both his maternal grandfather and his father were NFA members. His father came from a sharecropping family and never thought college would be part of his future. That all changed thanks to an influential teacher who led his father’s NFA chapter.

“My father was out plowing the field the summer before his senior year in high school. His vocational agriculture teacher came out and asked if he was going to college. When my father said ‘no,’ his teacher said he could help my father get into college,” says Alston, whose father went on to receive his agricultural education degree from North Carolina A&T State University.

That was the case for many Black students in the early to mid-20th century – the NFA and the organization’s teachers were responsible for Black students pursuing careers in agricultural education.

Something that surprised Alston as he was putting together the book was the impact the NFA had on the community, especially during WWII. The organization was used as a mechanism for encouraging rural families to can and preserve food during the war when food rationing was in place. It also helped advance and improve farming practices through adult farming programs offered to NFA alumni and adults.

Alston also was surprised by the sheer number of Black leaders who came out of the NFA, including North Carolina Senator Dan Blue, who serves as the current Senate Minority Leader. Blue was the past North Carolina Speaker of the House, becoming the first African American to serve in this role. Other notable former NFA members include retired Marine Maj. Gen. Arnold Fields and Lewis C. Dowdy, the sixth president of North Carolina A&T State University.

“A lot of former NFA members have said they were able to do what they did because of their NFA ag teachers,” Alston says.

While the NFA organizations were concentrated in the southern and eastern United States, Iowa State University can claim a tie-in to the NFA. G.W. Owens, who wrote the NFA’s by-laws, was mentored by George Washington Carver, an Iowa State alumnus and faculty member. Carver was a speaker at the NFA’s first national convention at Tuskegee University in August 1935.

The book also touches on the impact the NFA and FFA merger in 1965 had on the number of Black individuals involved in agricultural programs and teaching. Alston says at the time of the merger, there were 1,000 NFA chapters and 58,000 active members. Now, of the 700,000 FFA members nationwide, approximately 40,000 are Black (roughly 5%).

“We lost a lot of Black ag teachers and ag programs when the programs merged,” Alston says.

He considers it more of an absorption of the NFA program rather than a merger. The NFA’s emblem, which featured a cotton boll, and its colors, black and gold, were replaced by the FFA’s emblem, which features a cross section of an ear of corn, and its colors, national blue and corn gold.

Alston encourages people to read the book because it tells an important part of American history and shows how things really were – it wasn’t all “peaches and cream,” he says.

“This book was a labor of love. It enlightened me as a former ag student and now as a teacher of ag history,” Alston says.

Those interested in reading the book can preorder it online via Barnes & Noble or Target.